Conceptions Of The Priesthood… Why Fewer Are Accepting The Call

By JUDE DOUGHERTY

It is well documented that in the aftermath of Vatican II, vocations to the Catholic priesthood fell dramatically. They subsequently rose under the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, only to decline again since 2012.

Recent statistical reports are a cause for concern. There is a shortage of priests, notably in Europe and North America. Remedies proposed include an increased use of the permanent deaconate, the ordination of married men, abolishing the requirement of celibacy, and the ordination of women.

Conceptions of the priesthood differ and that may be the reason that fewer accept a call. Human nature has not so changed that fewer are capable of the self-sacrifice normally associated with the priesthood. In the past, a young man who declared for the priesthood could expect years of rigorous study, followed by a life of service and sacrifice in which he would be obliged to forgo many of the normal pleasures of life, forfeiting as part of a team a large measure of self-direction.

And yet until the recent past, the prospect did not dissuade. The numbers came. The life was demanding but the rewards were great.

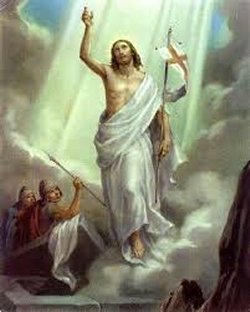

Ordination brought with it the power to consecrate bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, to hold in one’s hands the Alpha and Omega of the universe, to bind and loose in the name of Heaven itself, to proclaim, however feebly, the Word of God. As a mediator between God and man, the role played by the priest was unique, his powers awesome; and from the flock he served he shared the veneration due the sacred itself.

But then something happened in the aftermath of Vatican II. The council, in emphasizing the priesthood of all believers, led to the burring of a number of distinctions. The common apostolic vocation of all Christians which the metaphor sought to emphasize became instead a denial of the special character of the priesthood.

In a former time, Luther and Calvin has reduced the priesthood to a ministry, just as the sacraments themselves were reinterpreted and were reduced. But in spite of the reformers, the Catholic priesthood remained the distinctive institution created by Christ Himself.

Attitudes of the priesthood attend conceptions. When religion is conceived primarily as a code of values, and emphasis is placed on the performance of good works, priesthood may not even be required. On the other hand, if religion is conceived as the acknowledgment of and a payment of a debt to God, then worship and the things pertaining to worship are regarded as fundamental.

Obviously one conception need not preclude the other, but historically there are periods when the moral conception of religion has been exercised at the expense of worship. In our period when the moral conception of religion seems to be ascendant, religion has come to mean for many a practical idealism directed toward human welfare and social good. Religion is marked by vague sentiment, resolute goodwill and benevolence, and in a generous interest in setting the world aright.

This ethical conception tends to denigrate the things that pertain to the temple, to God’s majesty and to the adoration of that majesty. Attention to the ritual of sacrifice and to artifacts associated with the offering of sacrifice is minimized. So too is the spirit of asceticism and contemplation. One can find illustrations of this phenomenon if one remembers the iconoclastic and pietistic movements of sixteenth-century Europe. When worship is not central, other activity tends to take its place.

The Roman Catholic conception of the priesthood is grounded, as much of its teaching is, in the natural order. Noble conceptions of the priesthood antedate Christianity. By attending to these, especially to Hebraic and Roman sources, we may reach some useful insights appropriate for our day.

Viewed as a natural institution, the priesthood has an identifiable structure, an inner logic, integrity. Anthropologists tell us that priesthood is found wherever religion is found, and religion is found among nearly all peoples.

Though priesthoods vary from culture to culture, there are at least two key functions, one of which is associated with the priesthood everywhere and at all times, and the other for the most part. The one indispensable function which is universally associated with the priesthood is the offering of sacrifice. This requires the priest to be a master of ceremonial art and ritual. He is the offeror of gifts and sacrifices, presiding over the ritual re-enactments of creative, redemptive, or salvatory events.

As such he does not function in his own right. He is not a shaman or magician but a representative of the community in its relation with the gods.

The Roman notion of pontiff or bridge builder expresses this clearly. The priest stand as an intermediator between God and man, bridging the gap between God and man, bridging the gap between Heaven and Earth, a mediator between the sacred and the profane. He bestows divine blessings on the people and offers up their prayers to God and in some manner renders satisfaction to God for their sins.

The second function commonly associated with the priesthood, although not universally, is the teaching function, but this observation needs to be qualified. A certain kind of teaching is universal, namely, that associated with the offering of sacrifice. As a master of right, the priest is expected to pass on the ritual associated with his calling and instruct those wishing to worship in the proper way of addressing the object of their veneration.

But there is a more fundamental kind of teaching commonly associated with the priesthood, namely the perpetuation of the sacred traditions, beliefs, and practices of the people.

At certain times in the Hebraic tradition and the classical tradition, the priesthood is restricted to ritual functions. The priest is a professional, one who knows exactly how to perform the rites of worship according to prescribed rituals; he is not associated with either a teaching or prophetic role. Religious faith is passed through the family, from parent to child. Though moral virtue was expected of the priest, no training other than that necessary to master the ritual was required.

In the Stoic tradition we find a much loftier notion of the priesthood, as we do in certain parts of the Hebraic scriptures. In Stoic thinking, only a sage is truly equipped for the high calling of priest. In Philo’s account, the priest is the symbol of all that is highest in the domain of reason. In Roman society all priests were originally patricians. It was not until the publication of Lex Ogulnia in 300 BC that plebeians gained access to the collegium pontificum augurium.

Moral virtue in the priest presupposed members once admitted to the office kept their priestly character for life. Pliny speaks of an unperishable priesthood (Natural History XVIII 2). Persons with bodily defects were to be excluded, a ruling quite unusual in ancient sects.

If the Church is to be a beacon and not a weathervane, as the West endures a loss of faith, it will have to have within its ranks men of learning and culture who know their own traditions and who can defend them against challenges from without.

At times it takes considerable learning and sophistication to defend the obvious. This was understood in antiquity by St. Jerome, who experienced and wrote about the hardship connected with study. “The science of piety,” writes Jerome, “is knowledge of the law, understanding of the prophets, and full acquaintance of the Gospels.”

In the twentieth century, we find the German theologian Adolf von Harnack repudiating the work of Jerome, decrying the Hellenization of the Gospels, opting for the pure religion of love and social concern. The use of classical learning, he held, necessarily leads to ordinance, doctrine, and ceremony.

Unfortunately, one finds echoes of his What Is Christianity? in Amoris Laetitia.

Need we remind ourselves that the immediate heirs to the teaching of Christ were the apostles in whom we early find the employment of secular learning as they preach the Gospels? With the Fathers, explicit theologies are developed out of materials that are largely Greek and Latin in origin. That type of learning enabled them to speak clearly, make distinctions, and draw implications. That type of learning is today normally associated with classical philosophy, long an identifying mark of the Catholic intellectual tradition.